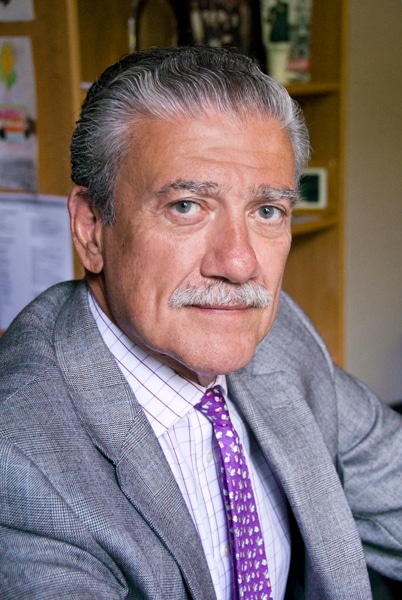

John Kemp has seen the Sistine Chapel. He and his wife, Sameta (Sam), have visited Tokyo, Egypt, and the Vatican. Their most recent trip to Paris and Rome was just another in a series of travels for the long-married couple, who are also parents and grandparents. Kemp has made each and every trip without the use of his limbs—a congenital anomaly left him without arms or legs. But through the use of artificial limbs, motorized scooters, and other technologies engineered for individuals with disabilities, the lawyer, partner, advocate, and CEO and president of the New York–based The Viscardi Center and Henry Viscardi School has pursued more than world travel; Kemp has dedicated his life to raising the standards and expectations for what a life with disabilities can be.

Kemp came to The Viscardi Center, an internationally recognized network of nonprofits dedicated to educating, employing, and empowering people with disabilities, in 2011 at the age of sixty. Kemp’s professional pedigree details a history of fighting for equality and acceptance of people with disabilities that very few can rival. The CEO was the 1960 poster child for Easterseals, an advocacy group for people with disabilities to which Kemp subsequently formed lifelong ties. The organization even asked Kemp to serve on its board of directors at the age of nineteen. “It was work with the Easterseals that really started me down the path of working on disability rights issues,” Kemp says. “Being asked to join a board with twenty-five adults was kind of terrifying, but it’s really where I got my start.”

Kemp graduated from Georgetown and immediately went to law school. During debate concerning the creation of what ultimately became the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Kemp testified before Congress, voicing his support for the legislation outlawing discrimination against those with disabilities. The legislation passed, and Kemp realized his expertise could be put to use. “I knew there would be a great need for information to clear up the confusion about how to implement these rules and regulations,” Kemp says. He and a partner created a consulting company that educated businesses on disability etiquette and disability inclusion best practices in the industry. “We were two twenty-seven-year-olds telling guys twice our age what to do,” Kemp laughs. “We thought we were hot stuff.”

The succeeding years would see Kemp taking on a litany of opportunities and challenges, forcing the young executive to grow up quickly. That wouldn’t be any more evident than when Kemp took on his first CEO role at the United Cerebral Palsy national organization in 1990, the same year the executive was able to help influence the passage of the landmark Americans with Disabilities Act. Success aside, Kemp still felt somewhat ill prepared. “I was forty years old, and I remember closing my office door on my first day and wondering what I had gotten myself into,” Kemp admits. “I didn’t know if I could even do the job.” Thirty years later, Kemp thinks it may be safe to say that CEO roles turned out to be a good fit.

“Our long-term goal is for every local dentist office to be accessible to all people in our communities.”

Though Kemp admits taking on a new role at the age of sixty wasn’t part of his career plan, the chance to head up The Viscardi Center just made too much sense to pass up. “My introduction to The Viscardi Center was literally Henry Viscardi, Jr. himself,” Kemp says. The CEO saw Dr. Viscardi speak at his own introduction as Easterseals’ poster child in 1960.

The disability advisor for eight US presidents and world-renowned advocate for people with disabilities impressed the young future leader, and Viscardi later sent the boy all of his collected writings on disability advocacy. “When I was watching Dr. Viscardi give this fire-and-brimstone speech filled with outrage about the low expectations for people with disabilities, my dad put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘That could be you one day.’”

Kemp’s father looms large in the success of his son. Kemp’s mother passed away when he was an infant, and the thirty-two-year-old federal highway administration official raised three children by himself with a mind-set that is progressive in its approach even seventy years later. “My dad believed that through education, almost anything was possible,” Kemp says. “He was an eternally optimistic and remarkable human being.” The CEO says his father read every single book that Dr. Viscardi sent, always looking to learn new ways in which he might provide more opportunities for his son.

Now Kemp is looking to provide more opportunities for everyone with disabilities, illustrated most recently by Project Accessible Oral Health (PAOH), a Viscardi Center initiative created to eliminate barriers to care such as insufficient education, inadequate reimbursement to providers, and unequal access to care. With dental care cited as the number one unmet healthcare need of the more than fifty-seven million individuals with disabilities, PAOH plays a unique role in connecting stakeholders committed to achieving oral health equity for the disability community. “There is a critical necessity for education around the important contribution good oral health plays in overall health and quality of life,” Kemp says regarding the initiative. “We must elevate and increase the health literacy around this social justice issue that up until now has not been sufficiently addressed or seen significant change.”

Project Oral Health comprises three pillars: policy; education of professionals, caregivers, and those with disabilities; and marketing and communication to tell the story of the broken system and how to implement solutions. The National Council on Disability has also identified this crisis through its chair, Neil Romano. At the time of speaking, Kemp had just returned from the Project’s second international conference, “Champions for Oral Health in the Disability Community,” which included attendees from across the US and around the world. “Our long-term goal is for every local dentist’s office to be accessible to all people in our communities,” Kemp says. “People with disabilities should be treated by professionals who are culturally competent to address the needs of people with a wide range of disabilities.”

Kemp also believes it is incumbent on people with disabilities to demand better quality of life for themselves. “We need to look for a longer horizon that includes work, family, and a home,” Kemp says. “The cycle of low expectation often begins at home, inadvertently, with parents who don’t know what they can expect of their children, but I feel strongly that these people need to be pushed. We have to be responsible for ourselves first.”

Our Guest Editor’s Perspective:

There are no words to describe the effect that John Kemp has had on the disability movement in our country. He is a charismatic leader, a fighter, an advocate, and an amazing mentor and friend. John sees what should be and works to make it happen. In the intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) field, we have known for years that medical and dental services are often not available because doctors and dentists have not had the training in specialized services that are needed. But John decided it was time to do something about the issue, particularly oral health, and set forth bringing in experts and policy people to work on a national agenda. And no one says no to John!

John’s dedication to the causes that are critical to people with disabilities is just extraordinary. But it is perhaps his warmth, humor, intelligence, and caring that set him apart from others. When John speaks to people with disabilities and their families, there is a connection that resonates within them. He understands their issues and has high expectations for what they can achieve. John once used the quote, “If not me, who?” in a speech, and he lives that philosophy every day.